December 11, 2018 From rOpenSci (https://deploy-preview-334--ropensci.netlify.app/blog/2018/12/11/treestartr/). Except where otherwise noted, content on this site is licensed under the CC-BY license.

I never really thought I would write an R package. I use R pretty casually. Then, this year, I was invited to participate during the last week of the Analytical Paleobiology short course, an intensive month-long experience in quantitative paleontology. I was thrilled to be invited. But I got a slight sinking feeling in my stomach when I realized all the materials were in R.

And so I, a Pythonista, decided I would spend some of my maternity leave writing R packages to try to blend in with students who had spent the month living and breathing R.

The best way to learn something is to apply it. And in phylogenetics, we have a lot of challenges to which we could apply a little R. We work with datasets that can be hard to visualize. The outputs of Bayesian analyses can be voluminous and tricky to summarize. Models themselves can be complex and incomprehensible. I had a particular task that had been vexing me: generating starting trees for large datasets and complex models of evolution. Many modern methods for estimating phylogenetic trees do so using Markov Chain Monte Carlo simulation, a procedure by which phylogenetic trees are sampled and evaluated under a particular statistical model of evolution (for a gentle, but rigorous, summary of MCMC in phylogenetics see this paper by Holder and Lewis). A reasonable starting tree (a tree from which an MCMC tree search is initialized) can improve the efficiency of MCMC-based phylogenetic analyses greatly, particularly in situations where we have lots of parameters and lots of missing data. A starting tree is used to generate initial values for an MCMC search. The starting tree is then modified throughout the course of the tree searching process. Each modification is evaluated to see if it is a better descriptor of the data.

Starting trees are often gleaned from the literature. Usually, a previously published phylogeny will be input as a starting point. In my research we combine fossil and molecular data, and we usually don’t have a published phylogeny for a set of taxa. I can’t simply pluck a tree from the internet and pop it into my analysis. I need a reproducible way to automate the process of generating starting trees. I am faculty at a primarily undergraduate institution, meaning many of my employees are just gaining their skills as computational biologists. Therefore, I need a reasonable way to get starting trees that is simple enough to be executed and debugged by undergraduate students who might not have their legs all the way under them. Tall order!

This is where treestartr came from.

From the user side, treestartr has four main utilities: to add taxa to a tree at random, to add taxa to a tree by guessing at taxonomy, to add taxa by hand, or to add taxa via a spreadsheet. All of these facilitate different aspects of the research, and I’ll talk about each in the context of how my students are using them.

🔗 Adding tips via dataframe

I’m presently working on a dated phylogeny of ants. Two of my lab members, Christina Kolbmann and Tyler Tran, are interested in fossil taxon sampling and its relationship to divergence time estimation accuracy and precision. Ants have tons of fossils, including multiple fossils in some genera or subfamilies. Many of them are preserved in amber, leading to a high degree of precision in placing the ants on the tree (For some stunning images of fossil ants, have a look at AntWiki, a community maintained Wiki devoted to all things ants). This is great - it means we have lots of data. This wealth of data allows us to ask big picture questions about what happens if we exclude parts of the data. One question we’re interested in asking is if subsampling fossils has deleterious effects on accuracy and precision. This is an interesting question because most fossil groups are much more sparsely sampled than ants. We can subsample our wealth of data to simulate different biases that are present in the fossil record of other groups.

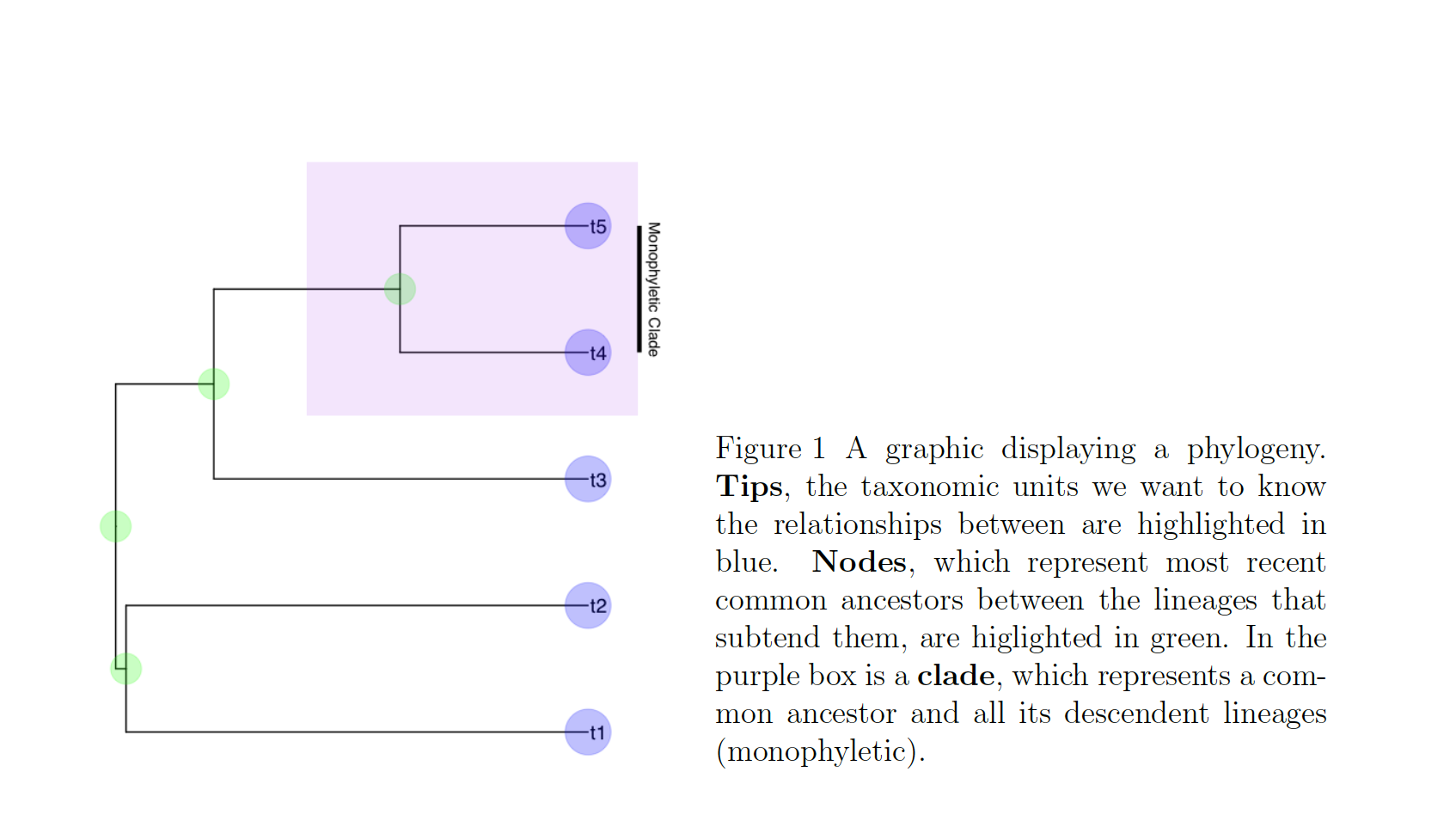

In these cases, we know roughly where on the tree might be a reasonable starting place to try attaching the taxon. In this case, we can use the function text_placr to read in a dataframe of taxonomic relationships. We can then use those relationships to generate a starting tree. An example taxonomy dataframe is below. In this data frame the two tips (if you’ve forgotten your phylogenetic terms, check out the above figure) to be added, Kretzoiartcos beatrix and Ursus abstrusus, are listed in the taxon column. The clade column contains tips that are currently on the tree. The two tips associated with Kretzoiartcos beatrix, Indarctos arctoides and Indarctos vireti, will form a monophyletic group with Kretzoiartcos beatrix on the generated starting tree. The three taxa associated with Ursus abstrusus will form a monophyletic group with Ursus abstrusus.

| taxon | clade |

|---|---|

| Kretzoiarctos_beatrix | Indarctos_arctoides |

| Kretzoiarctos_beatrix | Indarctos_vireti |

| Ursus_abstrusus | Ursus_arctos |

| Ursus_abstrusus | Ursus_spelaeus |

| Ursus_abstrusus | Ursus_americanus |

🔗 Adding tips via taxonomy

Tips can also be added to the tree automatically if there are other members of the same genus on the tree. The function present_tippr` checks the genus of a tip to be added to the tree against the genera present on the tree. If there is one match, the tip is added as a sister to its congener. If there are multiple members of the same genus, the tip is added subtending the most recent common ancestor of all members of the genus. This is a fairly handy function for adding taxa that are closely related to other tips on the tree - there’s no need to make a dataframe of species relationships.

🔗 Adding tips at random

For when you well and truly have no idea how the taxa you want to add to your tree should be added. rand_absent_tippr will add your tips to the tree … somewhere. In the datasets my lab works with, there are always a few fossil taxa with unclear relationships to the rest of the group. This function allows us to develop a distribution of starting positions for mysterious taxa.

🔗 Adding tips by hand

For the visual among us, absent_tippr opens a graphical user interface. Users can then see the computer-generated node label for every node in the tree, and choose the one they would like the added tip to subtend.

🔗 Mix and Match

For some of our workflows in the lab, we use multiple functions. For example, we might first place all the tips that have close relatives using present_tippr. Then, tips that represent more distantly related taxa can be placed via text_placr, and the leftover fossils added via rand_absent_tippr.

🔗 Why rOpenSci

I was a little unsure at first about submitting a package to rOpenSci. I’m a biologist, and while I’m computational, the idea that I might be a solo author on an R package seemed like I was, I don’t know, misrepresenting myself? I’m not some sort of big, serious software person. But the more I thought about it, I realized that that makes rOpenSci more attractive - that some serious people could help guide me in making this package. I want stable software for my students to learn from and use. And so I should ask for review. It’s appropriate and it’s good to ask for expert opinion.

When I was thinking of writing up this blog, I posed the question to Twitter:

are there other venues (outside or within traditional scientific journals) for R code review? My packages don't fall under scope of @rOpenSci and would probably need domain experts (plant biologists in this case)

— Chris Muir (@thegoodphyte) November 27, 2018

And I hope I can answer this question adequately. I picked rOpenSci because it was explicitly R (so the editor and reviewers would know best practices) and the guidelines and how review would proceed were very clear. And for a totally new experience of in-depth code review, being able to see where the effort was collaborative was helpful. I looked at other journals, but I liked that rOpenSci had biologists as editors. Because the handling editor (Scott Chamberlain) is a biologist, he had the ability to work with me to find reviewers (David Bapst and Rachel Warnock) who are serious experts in both R and the particular type of phylogenetics that I do. I suggested Dave & Rachel because I know I can collaborate with them, and they will be constructive and kind. But they will also really try to break the package and dig in to the meat of what software functions are required to support the science we do, and tell me honestly if my package is providing those functions. You can see they weren’t easy on me!

rOpenSci also has a collaboration with Methods in Ecology and Evolution. I plan to send a short software note there. It’s very nice to have the flexibility to send the paper to a traditional outlet like Methods in Ecology and Evolution, or to send it to JOSS, or to do nothing at all, if I didn’t want to.

🔗 tl;dr

Come on in, biologists. The water’s fine.

🔗 Future

I’ll likely add in more utility functions for parsing biological data for use with divergence time estimation. Particularly, I often work with RevBayes, which is a sandbox-like framework for Bayesian analysis of phylogeny and comparative methods. Our analyses integrate across fossil taxa from databases, molecular data from the literature and stratigraphic ranges. Each data source has special and unique quirks, and I’m always looking for ways to lower the bar for undergraduate researchers to be able to access these sorts of complex modeling frameworks. Please feel free to make a pull request or file an issue if there’s something you’d like to see added. I have a Contributing guide here outlining how to contribute.

🔗 Acknowledgements

David Bapst and Rachel Warnock reviewed this package, and provided immensely helpful comments. Scott Chamberlain handled the review. I’d also like to thank Jack Henry Wright Stinnett and Alice Wright Stinnett for being such good sleepers that I got to make the skeleton of this package while they napped:

Wrote a small workflow for generating molecular + morphological starting trees in python, but realized for upcoming use, it actually makes more sense to be an R package. Both kids are asleep, here we go. pic.twitter.com/ckouxLHUV7

— Dr. April Wright (@WrightingApril) July 5, 2018